Others views on society’s drive for constant growth

An excerpt from a larger upcoming essay on making things of value

Contemporary society’s drive for constant growth has not been the norm for human civilisation. For far longer, human civilisation has been driven forward by other impetuses.

The drive to survive. The billions among us who are not as fortunate as those reading this likely continue to be driven by this core drive. Per Netflix, so is Daniel Ricciardo.

The drive for salvation. The pious among us are likely animated by this impulse above others.

At other times, parts of human civilisation have been driven by the drive to explore, the drive for power, the drive for and other such impulses.

Some argue that the age of capital and industrial mass-production set the wheels of necessary growth in motion. I remember watching the lectures of David Harvey as an undergraduate. In them, I recall he argued that, in the long run, modern capitalism was incompatible with his view of the real world. Modern capitalism demands, he suggested, a 3% annual global GDP growth rate forever, but the world is finite. Its resources are finite. The value that can be given to its finite population is finite. How could the world possibly sustain a compounded annual growth rate of 3%?

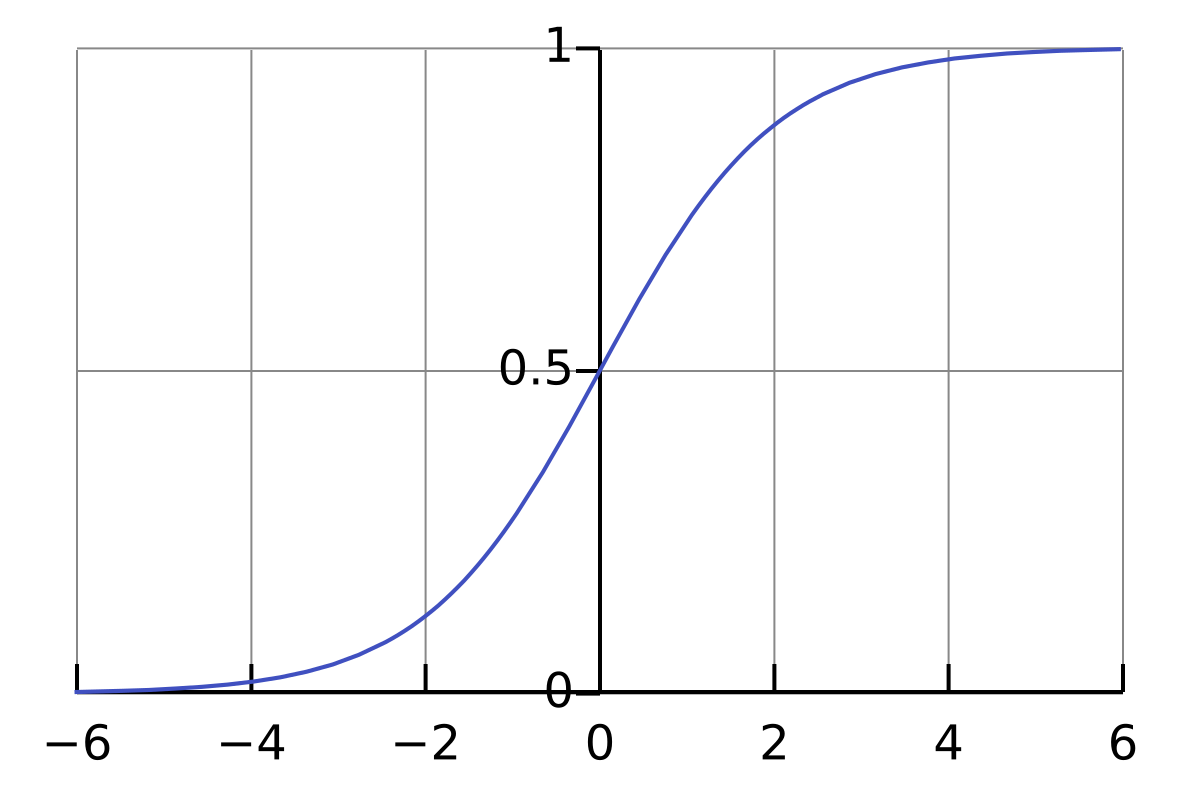

Uber-capitalist accelerationists like Elon Musk have since echoed similar views as folks like David Harvey, their ideological opposites. They argue, among other things, that the only way human civilisation thrives long-term is as a multi-planet species. Vaclav Smil bisects these arguments with the view that ‘no trees grow to heaven’, arguing that all growth – be it in organisms or human-made – follows a sigmoid curve.

Others take a more essentialist view and speak of moral decay – greed, gluttony, Sodom and Gomorrah. The post-War west, these ideologues argue, has since the 1950s championed a culture of overconsumption. Society’s obsession with growth is the core tenet of Americanism as a philosophy: the primary export of the twentieth century’s prime hegemon. Mad Men, A Few Good Men, Tom Cruise, the TV dinner. Some among them argue for a more atavistic lifestyle. Others argue for a collective utopia free of greed.

Others still argue that the drive for growth isn’t new. The industrial revolution did not invent growth; it accelerated it. Through a Eurocentric lens, this is true. But seen through an Asiacentric lens, the industrial revolution in fact slowed down centuries of growth within the geographical boundaries of modern-day China and India, which contained, before it, the largest economies in the world. De-averaging global numbers, therefore, tells a more complicated story.

More ideas on growth pessimism here. I, of course, am not a growth pessimist, but it’s important to note that there’s a rich tradition of that variety of thought.