A reading of Mood Machine by Liz Pelly

The only way for us to ensure the music we love isn’t killed off by streaming is to bring the music we love to the foreground

This is not a review of Mood Machine – the Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist by Liz Pelly. Before I take you on the sort of meandering walk through the jungle of context that is typical of my writing, let me introduce the book. Mood Machine identifies the several challenges that have followed from the growth of Spotify. These range from the financial challenges musicians face due to abysmal streaming proceeds to the collapse of active listening. I find a lot of these criticisms of Spotify fair (as I have discussed in the past) and I recommend the read (strongly). However, I disagree with some of its framing of the problem encapsulated by its byline. The following sentences from the last few pages of the book serve as good examples of the source of my discomfort. I’ll tell you why after you go through the meandering context that follows.

[W]e’re not having a serious conversation about the future of music unless we’re talking about public funding, cooperatives, unions, and international solidarity—and unless we reali[s]e that the fight for a more liberated and de-commodified cultural sphere is part of the broader struggle for a better world.

Luckily, the future of music is not something that was unilaterally decided in 2008 when the major labels struck their first deals with Spotify.

Ultimately, we can’t think about changing music, or changing music technology. That’s not enough. We need to think about the world we want to live in, and where music fits into that vision.

At the end of this essay, I will make with the following assertion: the only way for us to ensure the music we love isn’t killed off by streaming is to bring the music we love to the foreground, even if we choose to have the rest of our engagement with music happen in the background. This only happens if we pay for the music we love.

Qualifying my opinions (skip forward if you’re more interested in charts and frameworks)

Let’s start with why this isn’t a book review, and why I hope to never ‘review’ a book. I think the unqualified book review is dead. What I mean by ‘unqualified’ here is this: the book review that expresses an opinion about a book sans qualification about (not the qualifications of) the reviewer himself / herself is dead. If you have an opinion of Mood Machine by Liz Pelly that you think should impact mine, I would like to know what you think about V8 engines, robusta coffee, Gulmohar trees, notebooks, fountain pens, and the capture of Chandannagar by the French and British colonial armies. And capitalism. I would like to know where you stand on the matter of capitalism. I’m firmly in the ‘pro’ camp, while acknowledging that the global capitalistic order is very much in need of reform, and will likely always be. Additionally, in the context of this book, I would like to know what your version of the history of digital music is. Even a personal, emotional history would do. Maybe the view of an Indian music nerd who grew up in the 90s and 00s with very limited access to an open market of affordable CDs and cassettes will differ from yours.

Here’s the view of that nerd. When I think of Spotify, I compare it to Limewire and Kazaa, uTorrent and Pirate Bay. I compare it to the days of MTV Remix with Nikhil Chinapa, 94.3 FM, 107.1 FM. I compare it to the days of my neighbourhood music store – Planet M – with the CD tower, Rhythm House, and the neighbour’s elder brother with a Nero burner and a cylindrical stack of Moser Baer CDs. Finally, I compare it to a world in which none of the above would’ve existed had India not liberalised in in 1990-91, opening up the country’s economy to the internet, peer-to-peer file-sharing, torrents, MTV, privately-run radio stations, video jockeys, music stores, and CD towers. If it weren’t for these economic reforms in what was once a political economy that stifled progress, it’s more likely than not that I wouldn’t have been able to write this essay for you to read.

Other times still, I think of progress through the lens of a musician who spent his twenties playing in bands whose music was south of obscure, whose sound was inspired by socially progressive outsider music – post-punk, noise, metal, etc. In India, music like that had a puny system supporting it. I remember collectives like REProduce Artists inviting bands like mine to play live a few times. There were BYOB venues that would later go on to be vandalised by (allegedly) paid (allegedly) goons who objected to a variety of perceived cultural imperfections: the speaking of one language instead of another, the making of some specific sort of joke, the death of some sort of monolithic culture. These were narratives that always seemed alien to me. My city – Mumbai / Bombay – was, in my imagination, multicultural, cosmopolitan. If these sorts of insular attitudes were to have prevailed back in the sixties, for example, when migrants to Mumbai from Tamil Nadu – a state in the southern part of India from where my people come – were being threatened with mass eviction due to the Idli Dosa Bagao movement, it’s more likely than not that I wouldn’t have been able to write this essay for you to read.

See: progress means different things in different contexts; it means different things to different people. Technological progress – growth, if you will – is a complicated, scary thing. Its complicated, scary nature leads many among us to want to shut it down, reverse course. It’s an understandable instinct. But here’s my opinion, qualified with all the personal context I’ve shared above: I can’t imagine that sort of thinking working. The arrow of all the technological progress I have seen has pointed in a single direction; and that direction has – on far more than average – been accompanied by economic progress. The techno-accelerationists’ view may be that this is terrific / inevitable, so let’s dial technological progress up to 11. The techno-pessimists’ view may be that this is terrible / avoidable, so let’s dial technological progress down to 1. I’m going to try and take the – admittedly capital L Lame – view of a questioning techno-optimist.

The meat of the matter

First things first, I agree that paying artists fairly is without a doubt central to any business model surrounding music. And it certainly seems as though this isn’t happening when you see the following facts one after the other.

On Spotify, tracks must accumulate at least 1,000 streams within a 12-month period to be eligible for royalty payments. Eligible tracks appear to pay out at a rate of around 0.003 per stream on average.

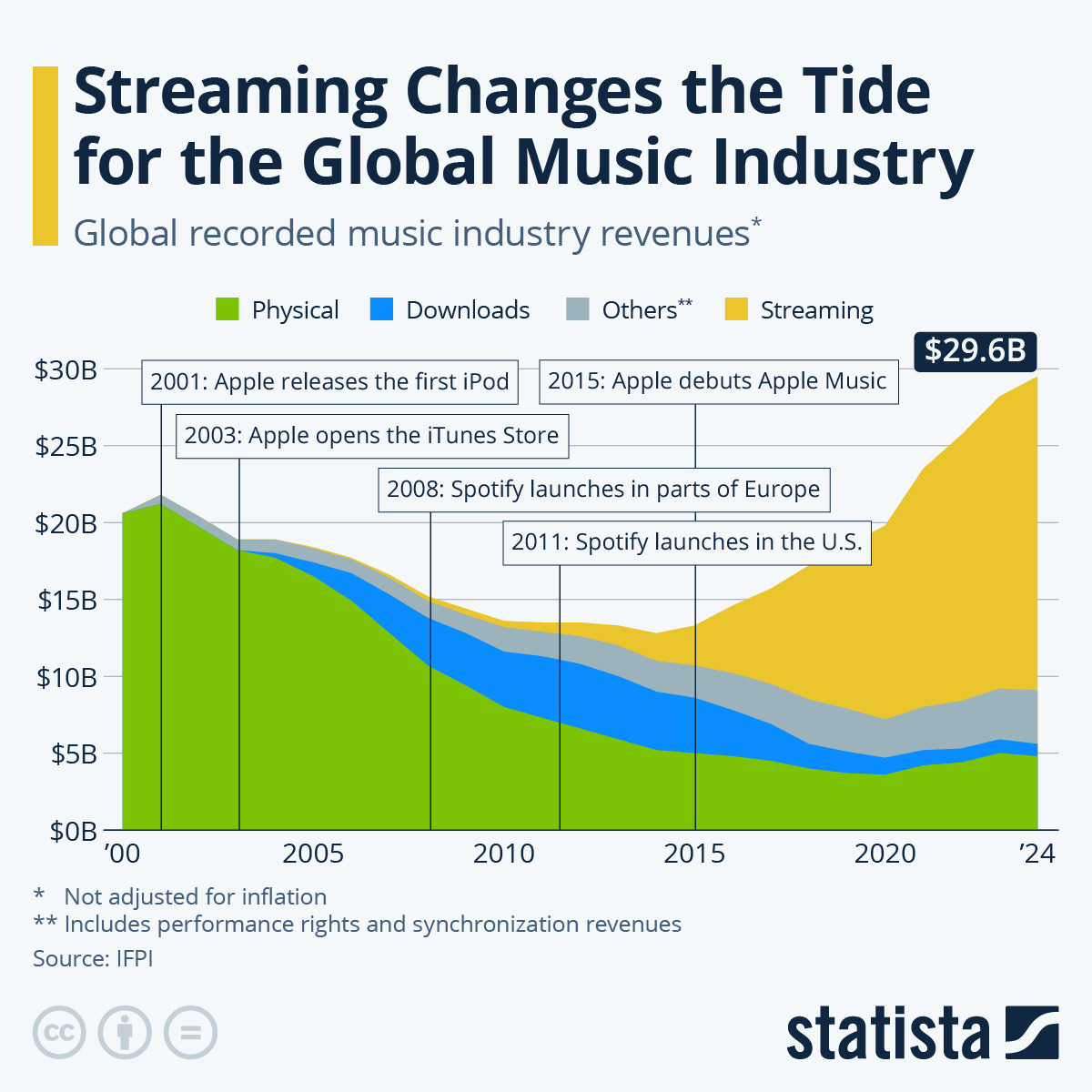

After a nadir in 2014, music industry revenues (not adjusted for inflation) appear to be seeing near-exponential growth (chart follows).

Spotify revenues have trended exponentially upwards y-o-y since 2015, with the business appearing to generate $2.5B in free cash flow (with adjustments) in 2024 (chart follows).