Daedalus: Or what I learnt from deleting all the apps off my phone for two months

First appeared as a serialised three-part journal on Stranger Fiction from Dec '24 to Feb '25, now combined (and updated) here on Substack for your reading pleasure.

PART 1 OF 3 / THE MIDDLE

1.1. An introduction

Today, on 23 December, twenty-two days since I deleted all non-essential apps from my iPhone, I had my first complete daydream in years: with a beginning, a middle, and an end. What it was about is irrelevant, what matters is the reappearance of daydreams in my life. The first since 2015: a year I spent as a full-time novelist. A year I spent daydreaming about futures I never ended up sharing with an ex-girlfriend, book tours that have since not occurred, and rock concerts experienced from the vantage point of imagined stages. To be fair, a few of those rockstar daydreams have since come true. In all cases, however, the daydreams ceased.

Had ceased, I should say, until today.

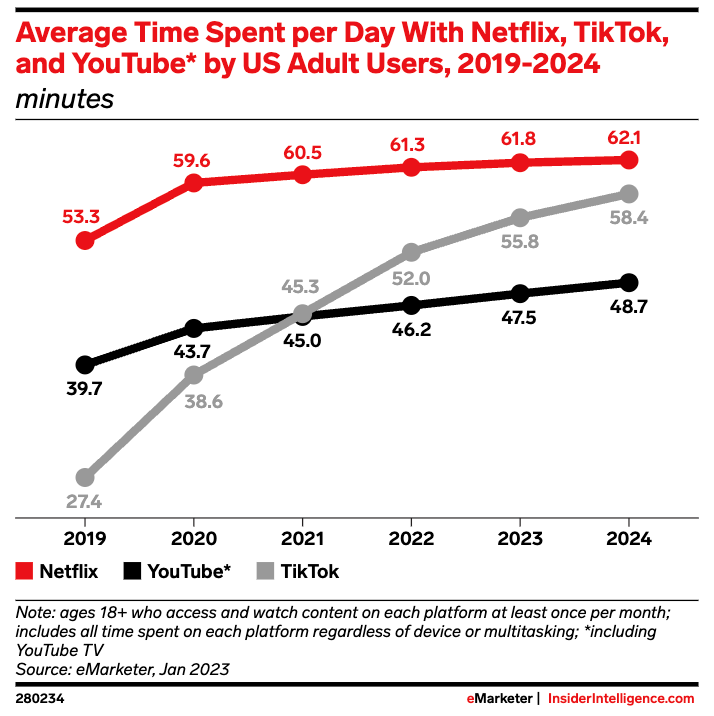

I tend to complicate Decembers. I preempt the imaginary line between years by taking stock of the year gone by. I evaluate my present moment. I make plans to build a better future. On the 30th of November, I stumbled upon a video that led me to this December’s big project. I got the idea from a video series by YouTuber Digging the Greats1, starting with a video titled Using This iPod For 30 Days Changed My Life. Its premise appealed to me on a fundamental level; my Wrapped 2024 playlist had just landed, and I was appalled at its state.

The only songs on it from the 2020s were: Hollywood Baby by 100 gecs, Taambdi Chaamdi by Kratex & Shreyas, Daddy and the Fields by Nourished by Time, and Introduction by Faris Shafi. Of these, I like, as music, only the tracks by Nourished by Time and 100 gecs. That’s 3% of my hundred most frequently played Spotify tracks in 2024. A world of music available to me at a cost subsidised near-infinitely by artists’ human need to create no matter how limited the commercial upside, and the best I could do is a lousy three tracks. This is not who I am. My first go-round writing on Stranger Fiction, my ‘back catalogue’ if you will, is proof. In December 2020, I was listening to the following albums.

I started off December 2024 being told by Spotify that I was listening mostly to Cake, the Strokes, Green Day, etc. Old stuff. Put another way:

“Lately I just don't know what to listen to. I could listen to absolutely anything, but I don't. Sure there's all kinds of playlists. Spotify even has a new AI DJ feature. But that's not what I'm looking for. Lately I have this deep feeling to just run in the exact opposite direction.”

– Digging the Greats

Once I was done watching the series, I was convinced: I was going to delete every non-essential app from my phone. Including – no matter how uncomfortable the idea made me – Spotify. (It did, however, take me a day of deliberation to reach that conclusion about Spotify.)

The obvious ones to go were social media time-sinks. This generation’s cigarettes – addictive, yet somehow still completely unrestricted. I recall having spent day 0 spending hours scrolling vertically through Reels, horizontally through AI-generated reposts of streetfights on Reddit, and then vertically once again through YouTube Shorts, the lowest form of doomscrolling. Instagram and Reddit were out right away. I wasn’t ready to sacrifice YouTube just yet; that came later, along with Spotify and Chrome.

With Instagram and Reddit went a whole host of past and future timesinks that had temporarily lost the battle over my mind to these two belligerents. Twitter, Threads, Pinterest, TikTok, other names I have since forgotten. These products represent a sort of attention deficit storefront display for my hyper-active mind. They exist only to quiet my brain when it asks – what if you run out of YouTube? What happens when there are no more reels of tiny dogs? What will you feed me then?

Then came the far more challenging decision to deem music streaming as non-essential. It was easy to get rid of Apple Music, next to no heartbreak deleting Bandcamp, Soundcloud, Mixcloud, YouTube Music, Deezer. These apps promised a near-infinite inventory of music in case a browser-enabled laptop was out of reach and Spotify and YouTube were insufficient for whatever musical need cropped up. In my context, these are to music streaming what Pinterest is to doomscrolling; ornamental. Spotify was tough. And it was not immediate; it took a day of active deliberation in my addled mind.

Third, video streaming. I gave no thought to deleting Netflix, Prime Video, Disney+, Starz, sport streaming services from every country I’ve inhabited / visited despite not having watched a sport in years. In hindsight, it must have been twenty to thirty apps, all barely touched, each and every one of them having lost the battle for my attention to the biggest of dogs: YouTube. Perhaps it was the shame of having spent over an hour on YouTube shorts just a day earlier watching every short posted by ColinAndMichael, but I found it a lot easier to delete YouTube from my phone than Spotify.

Finally, fundamentally useful apps that, in my addicted hands, had a high potential for abuse. Google Chrome – gone. ChatGPT – gone. Wikipedia – (with a great deal of reluctance) gone. What was once my primary source of information about the world was now a way for me to speculate about Ariana Grande’s relationship status in 2021 while on the pot. No more.

I grouped the apps that remained into only four folders – one for phone basics, one for utilities, one for work apps, and the fourth, hidden away, for apps on which I just couldn’t waste my time like my building’s community app. Then I turned my phone greyscale. Project Daeadalus, I called this experiment, my project for December 2024.

I have reclaimed much of my brain in the 22 days that followed that set of decisions. I, on average, spend nearly five fewer hours on my phone than I used to. I don’t feel phantom buzzes in my pocket at random points of the day. I have built new relationships (IRL) and deepened existing ones. I’ve enjoyed the following records.

Nala Sinephro – Endlessness

The Cure – Songs of a Lost World

Chat Pile – Cool World

Previous Industries – Service Merchandise

Gabe 'Nandez, Wino Willy – Object Permanence

Daudi Matsiko – The King of Misery

Viagra Boys – Cave World

100 gecs – 10,000 gecs

Sleaford Mods – UK GRIM

Jamie xx – In Waves

And, as of day 23, I have regained the ability to daydream.

1.2. Day 23

The results are, however, more nuanced than the previous few paragraphs may lead the reader to believe.

Our culture of digital excess is only part of a much larger culture of excess2. As a willing participant in this culture, I gorge myself on food that’s bad for me because I cook a lot less frequently than I should. I cook a lot less frequently than I should because cooked food is so readily available to me – delivered so much more often than not in under forty minutes. In theory, I could use the food delivery apps on my phone to make healthy choices: I could call in salads with ingredients I don’t have the skills to prepare well, bowls of fruit I don’t have the time to cut, three-ingredient sandwiches in rye bread I don’t have the training to bake. But I don’t call in these things because they simply don’t taste as good to the oversaturated palate as a meat patty and cheese between buttered potato buns. Or fried chicken. Or fried potatoes. Or fried anything.

I belong to the first generation of people that, in a median week, consumes more meals prepared outside the home than inside it. If done responsibly, there’s nothing really wrong with this, but the median member of this generation will also, on a median day, consume 30% more calories than the median member of their grandparents’ generation. We generate ten times more plastic than we know what to do with. And burn at least thrice as much fuel as the earth can capture.3 All of the above statements are just as true for me as an individual as they are for the slice of society that is the fortunate techno-elite.

By day 4 of Project Daedelus, I had my hands on a Shanling M0 Pro, an old microSD card I found lodged in a Nintendo Switch I no longer use, an old UGREEN 6-in-1 hub, and Bandcamp + the iTunes Store. Digital product consumption replaced by physical product consumption. Shiny new things: digital audio players, microSD cards, hubs, downloaded albums that are mine.

Attachment isn’t erased, but redirected. I know now – intimately – the environment of longing and wanting and having that’s created the conditions for my addiction. I also know that the best digital audio player for my needs is the Astell&Kern SP3000. I know that tracks downloaded off of Bandcamp – when formatted as AIFF files – sound significantly better than those downloaded off of the iTunes Store, or worse, the corners of the internet I used to frequent as a younger music nerd. But all of these sound better than streamed music. I know that if I replace my chi-fi in-ear monitors (IEMs) – nerdspeak for earphones – with Shures or Klipsches or something, I will be able to get a truer, richer sound.

There’s no app I can delete to fix the part I play in society’s ‘stuff’ addiction. I now have a more intimate understanding of it. And with that, I have a more intimate understanding of the gaping, growing, emotional void in me. Over the final week of what I intend to be a thirty-one-day experiment, I hope to build a life that’s better geared to filling it.

Sidebar

There’s no such thing as a decision; there’s only trade-offs. The choice of not having Reddit on your phone is yours, and it may appear to you that you’re making a decision to have a brain that isn’t always stimulated. But in the bargain, you’re choosing to be bored when on the pot. You can make the decision to delete Bumble from your phone because it’s just meaningless experience after meaningless experience, and that’s if you’re lucky. But if you do delete Bumble, you’re going to find that your dating pool shrinks to only the people you already know, the people they already know, and the one-odd new person you meet every now and then.

Alternatively, it may appear that the choice of having Reddit on your phone is a choice to have the same video thrown at you by a different robot every fifteen minutes. And the decision to have Bumble on your phone may appear to you as choosing quantity over quality, a constant reminder of the futility of dating, ‘it never really goes anywhere’, etc. These things may appear to be choices, but they’re not. They’re trade-offs.

When framed as a choice, so many decisions the computer in your pocket asks you to make appear to be decisions of convenience. They seem like no-brainers; why would anyone choose to experience inconvenience? The answer? For the same reason someone might choose to cook a meal over an hour, rather than ordering in a meal while spending that hour comatose in front of a screen blaring season five episode whatever of Friends – the one where everyone finds out – for the nth time in the last two years.

1.3. Why did I decide to do this?

I started this project on 1 December because ‘the algorithm’ was recommending me the same music over and over, and I, despite not really liking it, was blaring it into my ears unquestioningly. Twenty-four seven.

Also, I was spending much more time than I’d like to admit on apps I thought, even back when I had them on my phone, were meaningless time-sinks. I don’t want to spend as much time as I used to on unfunny reels and boilerplate memes. I don’t want to spend any time at all on TikTok. I hate what Reddit has become; it doesn’t at all resemble the community I joined more than a decade ago. And I hate that I flip through YouTube Shorts blank-faced, glass-eyed, before I sleep.

“I came here tonight because when you realise you want to spend the rest of your life with somebody, you want the rest of your life to start as soon as possible.”

– Harry Burns, When Harry Met Sally (1989)

When I deleted the apps from my phone, I thought I’d struggle with keeping myself occupied, with dealing with real-time emotions real-time, with fitting in with a reel-sharing Spotify-loving world. Instead, I’ve found myself more socially integrated and more in touch with my own emotions than ever before; more engaged. It’s like emerging from a trip that’s lasted over a decade.

The other side of the story is that dealing with real-time emotions real-time without a phone to distract you results in all sorts of self-realisation. And then there’s the question of attachment, how attachment steals attention to a much greater extent than any smartphone can. Rather than limiting my cuts to the space of smartphone applications, do I need to make a different sort of cut? Do I cut out stuff from my life? Certain people?

The ‘why’, it would appear, is attention, but not in the sense of focus. It’s about the choice of where to point one’s gaze – in the several liminal spaces of life, and in a broader sense. To immerse oneself in the ‘river’, so to speak, of life, rather than to dip one’s toes in it.

PART 2 OF 3 / THE BEGINNING

2. 1. Day 1

I’m thinking of deleting YouTube off of my phone. I spend too much time on it. But if I were to apply that thinking, why wouldn’t I also delete Instagram? Why wouldn’t I also delete Spotify? Wikipedia? All the apps save the ones I actually need to be a functioning member of society?

I’m a sucker for a ‘big project’. So often I’ve made a simple task the first step of a larger journey to ‘someplace far’, metaphorically speaking. Even the smallest of things start first with why, then how, then what. The thinking goes: starting with ‘what’ often misleads, direction is key. Maybe it’s because I’ve been trained to use frameworks to (what I believe is) good effect during the white-collar portion of my day. Maybe it’s procrastination driven by fear of failure.

Whatever the reason, I’m a sucker for ‘big projects’, the vast majority of which do not make it past day two.

I have been getting increasingly aware of how the internet’s current form has exacerbated my tendency to plan big projects that either never begin or fail right at the outset. By occupying every square inch of the attention I have to spare, it has made procrastination second nature. I, like most clear-eyed adults, have been asking myself how I might better use our species’ jaw-dropping advancements in information and communications technology as a tool, rather than becoming a puppet in its hands.

Last night, I stumbled upon a fascinating video by a YouTuber called Digging the Greats. It begins with his experimenting with using an iPod for 30 days to break free of the algorithmically driven chokehold Spotify has on his music listening habits.

In documenting his journey over the 30 days that followed, he hits touchpoints that will be familiar to many that have wondered about the impact their phones are having on their ability to function as fulfilled members of society. On the one hand, he discovers Digital Minimalism (and Cal Newport), the benefits of deleting social media from the phone, ideas about algorithms flattening culture and creating a sort of ‘lowest common denominator’ experience of it, etc.

On the other hand, he discovers how deeply integrated our smartphones are with our day-to-day – be it to access laundry or to play requests at a DJ set. In order to be a functioning member of much of the world today, you need your smartphone and the apps that you load on to them4.

On some level, we all know this, of course. Every cliché about the attention economy is true. The big ones:

Technology is a tool; it’s up to each one of us to decide how we want to use it.

Your attention is a product that’s being sold to large amoral corporations by other large amoral corporations.

Your self-control stands little chance against the trillions being spent to monetise your attention span.

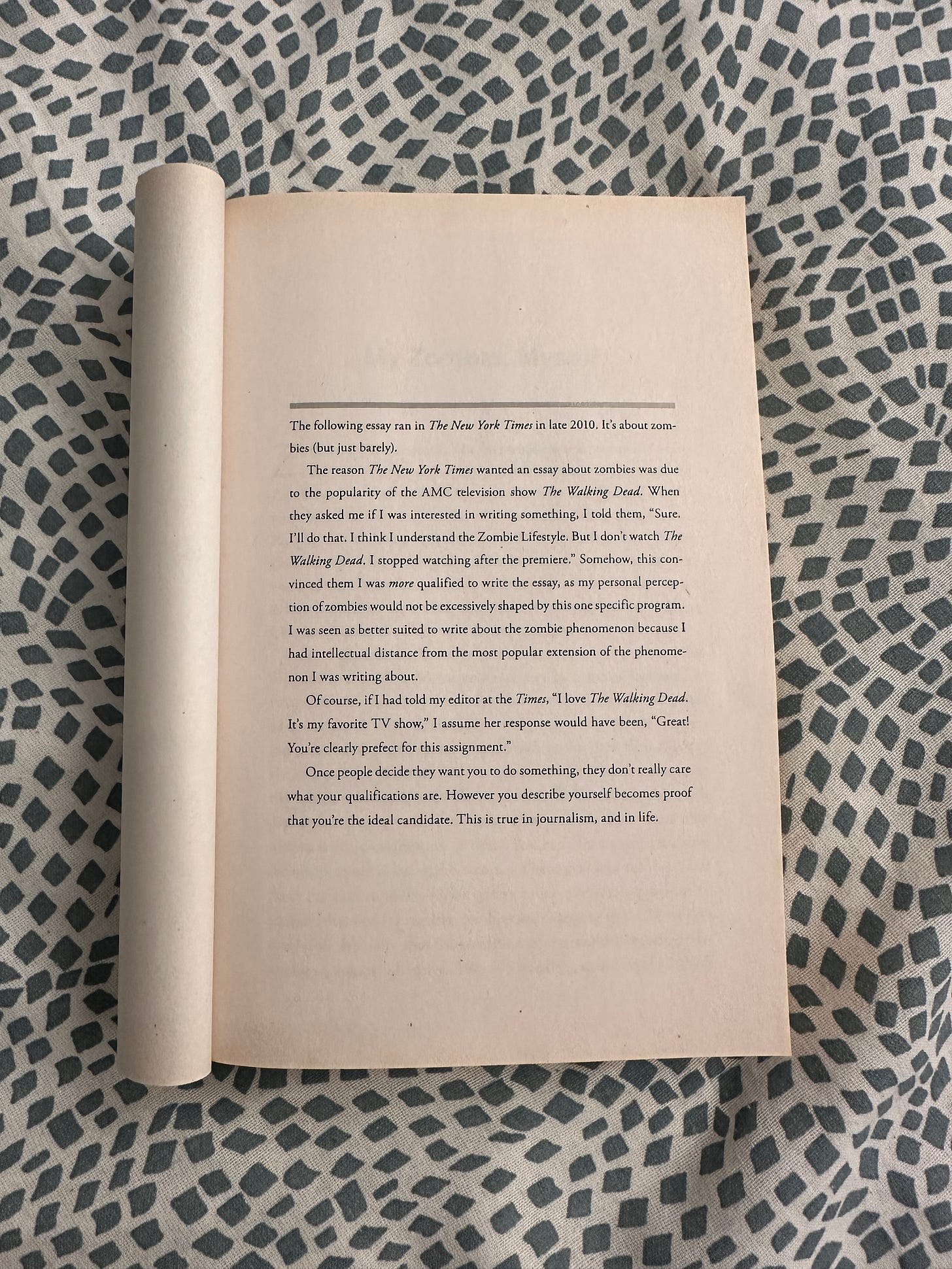

In fact, writing ineffective thinkpieces about the attention economy is now its own thriving economy – the attention economy economy, if you will. In being subsumed into the very culture it was set up to oppose, this subculture of internet criticism joins the ranks of several once thriving subcultures that are now part of the mainstream they once opposed. Ever had your inbox cluttered with emails claiming they’ll declutter your inbox, for example?

Inevitably, any writing that speaks to the dead-eyed consumption of throwaway content will find itself join the so-called ‘pantheon’ of ‘delete social media’ books, videos, reels, tiktoks. Any writing that attempts to help someone better themselves runs the risk of being labeled ‘self-help’5. Ultimately, the tragedy of living in a post-postmodern world is that self-reference is ‘baked in’ to most action.

All writing about this subject matter is ‘like’ the Social Dilemma.

In my case, all attempts to better myself are accompanied by imaginary montages of famous men playacting lowpoints for anonymous men to consume transferred improvement –

Mark Wahlberg, the Fighter, Strip My Mind by the Red Hot Chili Peppers

Joseph Gordon-Levitt, 500 Days of Summer, Vagabond by Wolfmother

Ryan Reynolds, Definitely Maybe, filmscore

All of human experience is a photocopy unless one makes a deliberate attempt to remind oneself of one’s status as occasional subject (in reference to Beauvoir). Unless one begins to see all writing as writing for an audience of one. All living as living for an audience of one. There is no audience but the self.

I’m not looking to add to this panoply of articles from millennials bemoaning the pitfalls of the defining trend of their shared adulthood. I’m looking to redefine my relationship with the internet of today. I’m looking to reclaim my attention. In concrete terms, I’m documenting for myself my experiment with eliminating non-essential smartphone usage.

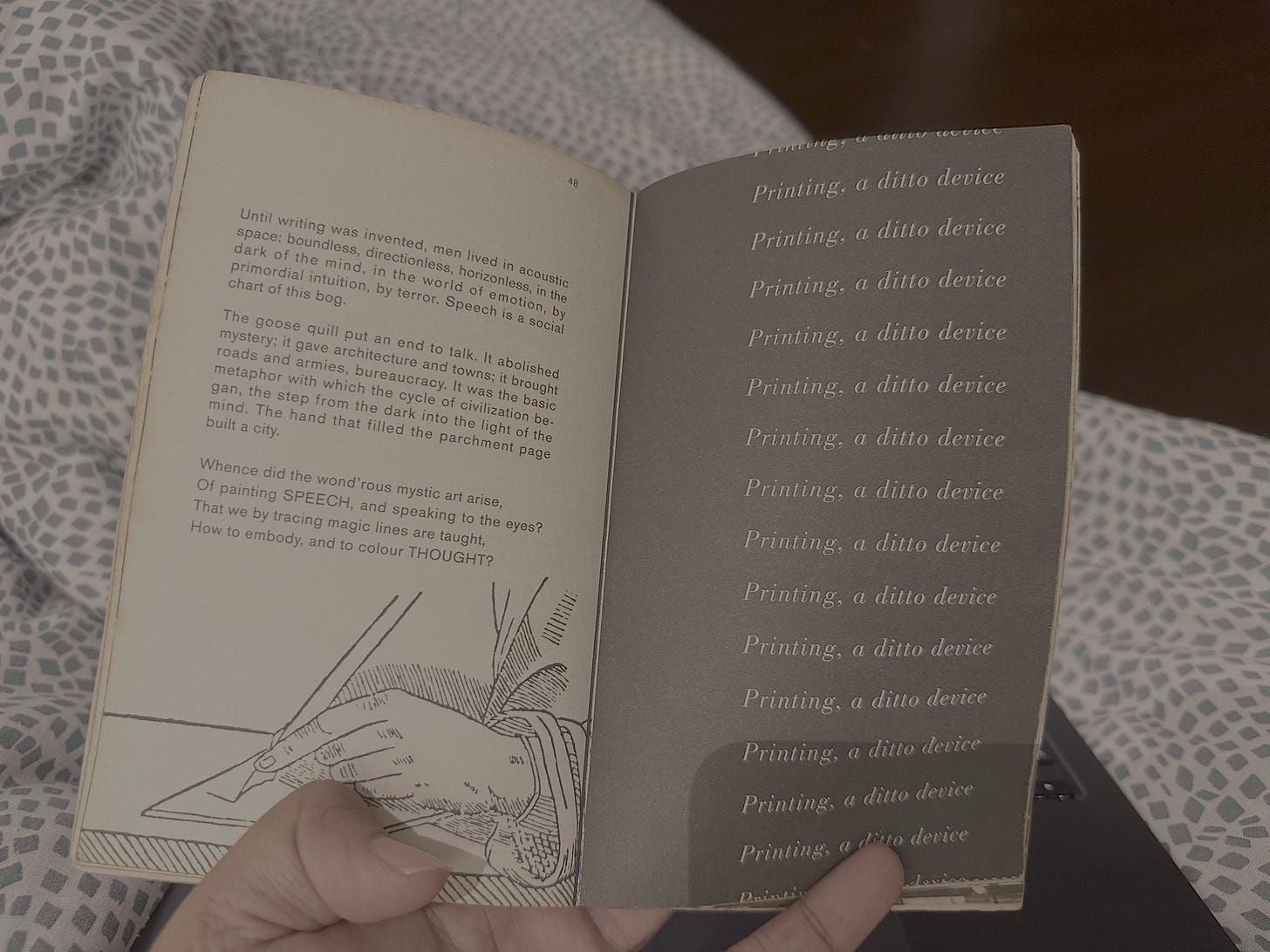

CONTENT. CONSUMPTION. COMMUNITY.

I no longer write stories.

I no longer make albums.

I no longer film videos.

I create content.

Or more accurately, I used to create content: before the tedium of posting, publishing, pushing said content completely consumed the joy of creating it, just as my original Instagram account was lost to Thai t-shirt salesfolk.

I no longer read stories.

I no longer listen to albums.

I no longer watch videos.

I consume.

I’m an object at the mercy of a much-maligned algorithm from which I’m separated by a screen. I’m not a subject experiencing the good work of an international community of artists from whom I am never distant.

At about the time the world – as we saw it – began to fit in our palms, all that’s sublime about the human experience began to be pornographised. It started with sex, then conversation, then all community. Everything of beauty was replaced by a poor substitute: made up of exaggerated versions of constituent parts that add up to lesser forms.

CREATE. CHERISH. COMMUNICATE.

And so I have done the following.

Deleted every app on my phone that didn’t serve a specific, expected, highly utilitarian purpose, e.g. Uber, apps for work, etc.

Disabled all notifications except those coming from family.

Grouped apps into four folders – utilities, core, productivity, and ‘careful’.

‘Careful’ = Spotify, YouTube, Apple Music, and Wikipedia. I should probably delete YouTube as well. This folder is where the risk lies. Besides, this folder is what got me started with this ‘big project’ in the first place.

Moved the phone to greyscale + Night Mode.

2.2. Day 2

Last night, I did two things over and above the prior list. 💩 is now serious.

One, I deleted the last remaining entertainment apps on my phone: that’s Spotify, YouTube, Audible, gone. The last remaining time-sink – Wikipedia – also gone. It’s ostensibly a place to learn, but has become primarily a source of gossip for me.

All that remains for me is to lose the browsers – Chrome (gone) and Safari. Already I’m finding it hard to imagine a life without browsers readily available on my phone. The panic and disorientation I experience when imagining a life – or rather, a month – without Chrome and Safari reminds me of the panic and disorientation I experienced last night when I deleted Spotify off of my phone.

When I did that, a single obsessive thought kept running through my head – without Spotify, how will I run?

WITHOUT SPOTIFY, HOW WILL I RUN?

In reality, Spotify has nothing to do with running; except that for me – and many others – running without music is unimaginable, and music is Spotify. It’s the sort of insidious link the television made with the family dinner in 1990s India; dinner, in theory, has nothing to do with television. Except for millions, it suddenly did.

My current experience attempting to write this very sentence without getting distracted by the noise in my head, the bustle of the café around me, the song blaring from its speakers, the sun, the sound of the till, the Australian sat behind me, the Brit sat in front of me, is proof that I’m also forgetting how to write without music. It could be that I don’t know how to be without music. That’s a larger problem.

Two, I’ve bought a DAP – a digital audio player – that can have its memory expanded to up to 2 TB; it gets delivered tomorrow. Less convenient, more expensive alternatives to Spotify exist for those fortunate enough to be able to afford them.

For those fortunate enough to be able to afford these alternatives, the price we pay for the convenience and affordability of Spotify’s streaming service is the value of intangibles that, at least to me, have begun to matter.

These are the hidden fees of Spotify:

Most of my favourite artists make a lot less money than they should.

The Spotify algorithm feeds me the same set of songs for every occasion while pretending that what I asked for is three identical ‘daylists’ a day.

I have a mostly compressed auditory experience of the world.

The insidious thing is that, commercially speaking, this is the only outcome for a streaming platform.

The number of songs on earth grows exponentially.

The number of people listening to music on their phone hits linear growth.

The only road to growth for Spotify – and the only chance in hell that the artists on there make any money off of the platform at all – is if every listener spends more time on it over time.

It’s also the best shot its algorithm at doing more than recommend Tomorrow by Silverchair in three playlists every day. I’m choosing the real world and real human beings (hopefully) as my music recommenders.

In the one day that I have spent without my AirPods locked into my ears, I have come to realise exactly how loud crowds are, and exactly how quiet being alone is. Spotify + the smartphone evens out the volume of all these experiences – in a sense, one experiences neither stillness nor chaos. With this experience-evener gone, my first experience is that of anxiety.

2.3. Day 3

THE PERSONAL IS THE POLITICAL

Four conclusions lie at the centre of a deeply personal social anxiety I have experienced since I was a child. Be funny. Be insightful. Be fun. Be ever-available. Smartphones made this worse.

They didn’t make me socially anxious; in 2008, which was before I had a smartphone smartphone, I feared missing out more than the average seventeen-year-old. It would be more accurate to say I feared being left out, being left behind. It’s important to draw the distinction between missing out and being left out. Truth be told, most things that lay at the other end of staying up late, always being available, are things I was always okay missing. It wasn’t my interest in these things that mattered – it was being chosen. The fear wasn’t that I’d miss out on something significant or fun – it was that I’d be excluded.

The smartphone took these nascent – addressable – fears and blew them up: not only for me but also for others. What if there’s something amazing at the end of my fifteen hundredth scroll of the day? replaced What if there’s something amazing at the end of another late night? Wouldn’t it be better to first fill in the large empty spaces of life with things that lead up to ‘why’ and ask what’s lost when they’re filled up instead with what-ifs?

DO FOOLS RUSH IN?

Adult life, in many ways, attempts to answer a question that’s as fundamental as the question of economics: how is a finite resource – time, in the case of adult life vs. money, in the case of economics – best allocated? Much of adult life’s most interesting questions arise because we know it ends. An unending life – immortality – would allow for endless luxuriating, and would therefore be animated by an entirely different set of concerns from the ones we currently face. That I get to ‘dip my toes’, as it were, in the ‘river of life’ is, without question, a cosmic miracle.

One’s experience of this might evoke either happiness or sadness, but in both those experiences is contained a miracle: the fact that, as a conscious being I can string together symbols that activate it in your head your head-voice concatenating a set of sounds that mean – approximately – the same thing to both you and me is nothing short of a miracle.

To ‘immerse’ oneself in this ‘river of life’ is to surrender to this once-in-an-eternity experience. All efforts towards such surrender – especially from the chronically anxious and fatigued – are worthy. However, one must never mistake oneself for the river. Any attempt to experience all of life is futile and self-defeating. Those that fight the enormity of life, struggle against it, and are eventually overwhelmed with ease. Time is a limited, precious, resource. If you were to fully accept this world view, adult life, you would likely find, has no decisions – it contains only trade-offs.

The question relevant to ‘Project Daedelus’ as I’ve come to call this endeavour is – what rushes in to fill the vacuum left by no longer numbing my mind with my phone?

This isn’t only a question of the smaller moments spent in the backseats of cabs, in queues at checkout counters, in dead spaces in conversation – the liminal spaces that riddle life. This is a question of how those five – or more – hours that bracket a workday might be better spent in service of the ‘why’ of life now that I’ve committed to ridding myself of my smartphone habit.

PART 3 OF 3 / THE END

I’ve read a lot more books in the two-odd months since I’ve changed my lifestyle around my phone. It turns out there's some truth to that tired cliché about reclaiming one's attention span. Since December 1st, I've read:

Digital Minimalism (2019) by Cal Newport

Dopamine Nation (2021) by Anna Lembke

The Art of Loving (1956) by Erich Fromm

The Contrarian: Peter Thiel and Silicon Valley's Pursuit of Power (2021) by Max Chafkin

In Defence of Food (2008) by Michael Pollan (re-read)

Willpower (2011) by Roy Baumeister & John Tierney

Doppelganger (2023) by Naomi Klein

The Virgin Suicides (1993) by Jeffrey Eugenides (re-read, abandoned within the first 50 pages)

Orbital by Samantha Harvey

Yellowface by RF Kuang

The Vegetarian by Han Kang (re-read)

Everything we do is at least half for show. Even when nobody’s watching, we’re often secretly auditioning for the love, the admiration, the warmth of others. Imagining nods of imaginary approval from uncaring cities outside open windows.

Perhaps it began with the ubiquitous TV set, Warhol: everyone wants their fifteen minutes. Maybe since we could witness everyone's fifteen minutes unfold in our palms, second by mundane second, we've begun to behave like we're always in the thick of ours.

More likely, it precedes all of this. In Victorian England, for instance, table legs sat covered with white cloth in empty rooms, projecting sexual modesty to non-existent guests. Forever, people have policed their private lives out of fear of neighbourhood gossip, even when no neighbours were watching. Man as social animal, ever afraid of ostracisation, ever driven by the desire to be accepted. The smartphone didn't create this phenomenon, it just amplified it. A change not just of scale, but of kind.

3.1. A DESIGN FOR LIFE

I half-searched for missing kudos in my empty apartment when I first purged my phone. At least half my screen-time in the week that followed was spent showing friends, family, acquaintances – anyone who'd look – how low my screen-time had become. And when the compulsive phone-checking finally ceased, it was partly replaced by me picking up the device just to admire its minimal, greyscale aesthetic. I worried: the thing with performances is that they eventually end; reality catches up.

But then things changed; a sort of calm took over. Forty-odd days past the stipulated end of my ‘experiment’, I haven't felt compelled to reinstall any of the deleted apps. I also haven’t felt compelled to rail against technology; I’m far more integrated with emergent tech than I used to be before I began this experiment, and I still use my phone; just more deliberately. I'm losing something – and we'll examine what that is – but it hasn't felt like loss. Instead, it feels like time gained.

It's difficult to overstate how profoundly this reclaimed time has shifted my perspective on life. As I started putting this together for an audience (of one, I have to keep reminding myself) I hinted at the changes I was beginning to notice in my relationship to attachment. I wrote about my being a symptom of a larger societal addiction to stuff. How my digital audio player (DAP) came to symbolise, in object form, this journey of digital decoupling. I wrote also about my fear of being left behind – left out of plans, excluded. How the smartphone, with its promise of endless connectivity just exacerbated these fears. Why is nobody texting me? Why is nobody inviting me to the cool shindigs everyone else seems to frequent? Like the pre-smartphone seventeen-year-old who aimlessly hung around his friends fearing social isolation, I had grown accustomed to picking up my phone over and over again, hoping to find signs of being a part of something bigger at the bottom of a text exchange, at the other end of a shared reel, in a missed call notification.

Just as deleting Spotify prompted the quick procurement of a DAP, complete with downloaded albums and an obsessive quest for the highest quality audio, the reduction in phone time created a vacuum that I rushed to fill with frenetic social activity. It’s what men with a happy single life do, I rationalised. Late nights and groggy mornings punctuated the first three weeks of my thirty-one-day experiment. Deleting these apps is making me more social, I insisted. That's good, right? A good thing – until I stumbled home at 6 AM on a Friday, having been out every single night for weeks. My diet: a veritable smorgasbord of bar nibbles and drink. My exercise regimen: a relic of an increasingly distant past. My mental state: shaky.

Later that Friday, a friend intervened. Sat me down and asked if this was really the life I wanted to be living. Suggested I slow down.

When I had decided to delete all the trash off of my phone, I was already deep in a crisis. Forces at work had conspired to make me miserable and had succeeded, largely because I'd allowed them to. A relationship had ended abruptly, albeit justifiably. Outwardly, I began clinging ever more desperately to anything that made me feel part of a community. I was perpetually out. Always fun. Always available.

Always connected. Always on my phone. There’s a reel received. She loves me. There’s a message received. He loves me. There goes my phone, there it buzzes, there it rings, there it pings. They love me. They want me. They need me. They need me more than I need them and they will never, never, ever leave me.

3.2. VIRAL

Covid broke us all. We seem to have descended into a sort of collective amnesia about those years spent distanced from each other, experiencing human connection almost entirely through screens. Even those of us fortunate enough to not have lost loved ones to the disease spent the first six months alone, closed off, scared. Many lost jobs, saw relationships crumble, fell into seemingly endless spirals of boredom, frustration, and despair.

It took reading Naomi Klein's brilliant Doppelganger to remind me that yes, it had happened. Covid had happened. And it broke us all. It certainly broke me. I experienced a layoff, a relationship's dissolution, a spiral that seemed without end. And I was among the most fortunate. As the pandemic gave way to life after it, I struggled with social reintegration. People's intentions became inscrutable to me, especially in areas where I'd struggled most during the pandemic: romantic relationships, work. I experienced the alienation that comes with imposed long-term isolation, the anxiety that comes with forced reintegration. The world seemed riddled with post-pandemic maladies, and every thinkpiece in my carefully curated feed tempted me to abandon nuance in favour of simple explanations. I didn’t see this new strain of social anxiety coming. At thirty – a writer/musician/commercial director – I felt like a more helpless version of that seventeen-year-old student I once was. A more potent variant of a decades-old anxiety. I understand this vulnerability now, but then it blindsided me. Perhaps I lacked the words for it, or perhaps because we were all experiencing a similar thing, I didn’t see the experience as individual.

Or maybe it was because my screen served as a constant reminder that I wasn't alone.

Maybe much of the doom and gloom that seems to punctuate our zeitgeist is fair.

But we don’t give ourselves enough credit, both as individuals and as a collective, for how we rebuilt the social ties those years we spent apart strained. I’ve seen Zoom get a bunch of credit, high-speed internet too: for allowing us to stay connected despite not being able to be physically proximate. Vaccines and mask mandates get a lot of credit from some; their lifting, from others. The sheer resilience of the human beings fortunate enough to have made it through those dark and trying times? I’ve seen very little coverage to that effect.

Maybe it’s too twee for the era of outrage. It’s easier to pin the virus on people and our recovery on technology, perhaps. Or maybe we don’t say it because it’s obvious. Of course we’re resilient, it’s taken for granted; assumed. Just like the cosmic miracle that is our ability to communicate with each other is taken for granted. My personal experience has taught me the opposite approach is likely the best. I, like many people I know, have displayed tremendous strength to become the person I am today. Long-time readers may find it odd for a writer of dystopian fiction and murky music to be saying this, but I assure you it’s true. And the same is likely true for many of the thousands of long-time readers reading this.

It’s also true, however, that the wear-and-tear of having gone through the journey is real. Attachment, fear of isolation, and finally, the red herring we were sold to fix those problems: being glued to the computers we carry with us everywhere we go.

3.3. 1 STEP

Every journey to someplace far begins with a single step.

When I started on this journey on the first of December, I thought of it as a month-long experiment in decluttering my phone. Now that I’m in possession of a decluttered phone, a digital audio player, and a music collection, I see this as part of a longer journey of decluttering my once-addled mind. And technology, when used intentionally, actually enables that, instead of getting in the way.

In the forty-odd days since the conclusion of that experiment, I’ve seen no immediate reason to reintroduce any of the apps I’ve lost, and I’m beginning to see compelling reasons to lose a few more (and gain entirely new ones). However, here’s the interesting thing: the apps on my phone, my screentime, the time I spend on my phone, none of it is an area of focus for me anymore. The marginal gains in attention I will make from continuing the cull will likely be overshadowed by the downsides of losing functionality. Project Daedalus comes to an end.

What replaces it is a broader design for life. Yet again, I’ve allowed a simple task to become the first step in a journey to ‘someplace far’, metaphorically speaking. Old habits die hard.

Yours,

Akhil

Mumbai (or Bombay, as you like it), 8-Feb-2025

More on this in part 2.

The digital minimalism thinkpiece has taken the place of the material minimalism thinkpiece as contemporary cultural cliché. A disclaimer: everything that follows is a statement on the fortunate among us, of whom I am one. Every statement I make about excess excludes the hundreds of millions that live in conditions of unimaginable scarcity. I will run up against some of the conundra humanity’s seemingly dual existence creates, but this isn’t the forum to discuss it directly, and I don’t have the skills to do so.

‘Emotional facts‘. Actual numbers may vary.

I become acutely aware of this every time I fly back home to India, where the whole system of banking and payments has moved to the phone through the widespread adoption of UPI and the government’s phone-first banking schemes. The smartphone will soon be seen as a necessity.

Of every form of writing in the world, I find none more repulsive than self-help. Is it even ‘self-help’ if it’s someone else doing the writing? Isn’t it just ‘help’?