Ready for Consumption – Part 1/2: The Making Habit

What making music has taught me about product, market, and fit

An introduction: The emotions of taking a product to market

When I started Milk Toast – an end-to-end growth solutions company – a couple of months ago, I expected to face a few challenges with establishing product-market fit for the sorts of companies with whom I wanted to work. Whittling down a never-ending features list, building a product rather than a list of features, establishing robust delivery channels, pricing, things of that sort.

However, so far (it’s still early days), the hardest part – far and away – has been answering the following question.

When does ‘ready’ mean ‘ready for the public’?

There is, of course, a hard-nosed, quantifiable way to answer this question. Product gurus from around the world have courses on every available platform priced at anywhere between 0 dollars and 100k dollars answering product-market fit and go-to-market strategy questions like this one in hard-nosed, quantifiable ways. A summary of answers: 1. define your minimum viable product (MVP) as a fixed goalpost; 2. track sprints against the MVP’s defined feature set; 3. define behavioural and qualitative metrics to track engagement and repeat use (a product is more than a list of features); etc. Depending on one’s preferred mode of learning – podcast, book, online course, video – there are plenty of resources extolling the virtues of plenty of specific frameworks.

My experience – as founder, as advisor, as investor – has been that most people smart enough to start up, amass teams, create value for customers, team members, investors, advisors, are smart enough to have figured out most (if not all) of the hard-nosed quantifiable ways to answer this question. Most have read the books. Listened to the podcasts. Avoided the LinkedIn posts. They are aware of how they would like their ‘monthly active users’ metric to relate to their ‘daily active users’ metric. They’ve probably done all this product-to-market work at an organisation whose equity rested majorly in the hands of others. They’ve probably taken several products to market themselves.

But there’s a unique challenge involved in taking a product you have built to market, and that’s this. The distance between the product and the market is often the distance between the heart and the brain.

I’m not the first person to have figured this out. However, whenever I see this problem discussed, it’s treated as either infinite or infinitesimal, when in fact it’s neither. It’s a large, but solvable problem, and as with most matters of the heart, the best way to discuss solutions is by way of narrative, not to-do lists. It’s why we have romantic comedy movies, not romantic comedy frameworks.

This essay’s narrative is about my own experience making music and trying to take my music with the yet-to-be-released Out of the Hermitage project to market. In telling this story, I hope to shed some light on my hypothesis on breaking the heart-brain barrier in taking one’s own products to market. In this first part (the second part will be out next week) I talk about the making habit.

My experience making Out of the Hermitage, or: the making habit

Starting 2021, I’ve been recording music for release as part of a project called Out of the Hermitage. Covers, originals, hours of material. I’m at my most peaceful when I’m recording and composing music. The mechanical aspects of putting together a song put me at so much ease. The song’s arrangement, its composition, the production of its layers. A texture shows up here and the brain goes off: how about adding in that layer? The snare sounds just a little off there and a voice in the ear says: how about lowering the gain on the high-range in the EQ? Midway through recording a song in my bedroom studio, alone, I experience something akin to ego death. It’s happened so many times that I’ve come to believe it’s the closest thing to peace I experience.

I don’t really think I experience ‘peace’ when writing. For me, writing has come to resemble the opposite force: total self-expression. It isn’t exactly peaceful to express yourself so totally.

With writing, you can’t express your sadness as a layer of string pads. You must find the words for the butterflies in your stomach when you think about someone with whom you’re falling in love: an arpeggiated acoustic guitar will not work in lieu of words. When I express myself as totally and specifically as I do with writing, the audience is never truly distant.

There’s a famous writer (I don’t remember who, but I think it might be Zadie Smith) who once spoke about how the decline in interest in the written word liberated her, helped her write more freely, and I find truth there, but still the audience is never truly distant when I’m writing. Given I’ve never depended on writing to pay the bills, make ends meet, put food on the table, pick your go-to phraseology for making a living, I’ve refused – steadfastly, stubbornly – to change the way I write. My journey of writing has always been a journey towards increased authenticity. A self-learning goalseek algorithm with one end in sight: ‘my voice’, whatever that may be. Despite that, the audience was never truly distant. Ever since I started writing seriously in college – in this dense, idiomatic style, no less – I have intermittently wondered what sort of audience reads my stylistically anomalous prose. I have engaged with the audience. That engagement has improved my writing.

With music composition, however, I have never had to think about any of this. I just pick up the guitar or the bass or the keys or the mic and just get started. At any given point, there’s a ‘sound’ in my head. When it’s time, I turn on Logic and hit record. There’s nothing more to it: no meta-narrative, no camera floating over my head pointing me-wards, scanning me. I completely lose track of time, completely lose track of ‘performance’. I never seek to compose music better than I did the last time, or more authentically than I did the last time.

That’s how it differs from swimming: another brain-clearer. Head underwater, feet flapping, arms alternating, my brain clears in a very specific way when I swim. Much like with music composition, when I’m swimming, I find it hard to think about things that aren’t related to swimming. On a stroke, my palm crashes on the surface of the water flatly and I think: I shouldn’t have done that, I need to angle my wrists better for entry into the water. As a righty, I privilege breathing over my left shoulder over breathing over my right. I will go an entire mile not breathing once over my right shoulder if I’m not deliberate about my breathing, so I’m always thinking about it. I’m always wondering whether my legs resemble flippers, wave like, or see saws, stiff. At what pace am I swimming? Am I faster than I was the last time I was in the pool? Has my technique improved? Which lap is this? The twenty-first? Let me check my Garmin. Can’t do that while swimming. Just like when I’m composing a song, all I’m thinking about is this thing I’m doing: so, these two activities do have that in common. I am, therefore, often tempted to think of them both as being meditative activities. Here’s the key point of difference: I find thinking about swimming when I’m swimming more stressful than thinking about to-do lists or that client meeting that is guaranteed to go poorly or that invoice that’s pending payment. I find what I think about when I’m thinking about swimming to be more stress-inducing than anything else I’m doing. It feels like my brain is Clint Eastwood in Million Dollar Baby. My body is the championship boxer played by Hilary Swank. When in reality, I’m just a guy in a pool who is physically unperturbed but mentally destroyed by a thirty-minute swim.

That’s not what it’s like when I’m making music.

Yeah, I’m not thinking about anything other than the music being made, and yes, I’m mostly thinking about what I can change, what I can improve, but not like this. I don’t know what it is, but the stakes appear to be a lot lower1. The stakes when I’m composing appear to be a lot lower than the stakes when I’m swimming. I’m sure runners, lifters, those who do Pilates (pilaters? pilots?) feel the same way. The pressure to outperform in an activity that, in principle, is intended only for oneself. The pressure even just to perform, really. Fitness as performance art. Maybe even where there is no audience, some of us see an audience. Maybe especially then, because if something is meant to be done only for oneself, the aim of it must be to improve ourselves as individuals, and then – especially then – the work we’re doing is on ourselves, the audience is everybody. Maybe our modern moment has created only two types of individuals: the overdriven and the catatonic, as David Foster Wallace had predicted in Infinite Jest. And those of us who are naturally ambitious are now overdriven, stressed to our eyeballs, brow-pits the size of saucers, hustling our heaving bodies off this mortal plane.

That’s not how I feel when I’m composing music. The stakes appear to be reasonable. They are the right size. There’s no such thing as universally good music. There’s no such thing as universally terrible music. There’s music I like. There’s music I don’t. That’s it. I can listen to a song I’ve made and say: I like this. Similarly, I can say that I don’t. And that’s the end of that. I can go about my day with my sense of self intact: neither inflated through internal comparisons with Bach, nor deflated through internal comparisons to XX (insert my list of least favourite musicians / bands).

If that’s true, why has the idea of releasing the songs from Out of the Hermitage daunted me since 2021?

Why I find publishing music stressful, or: why I think the world is unfair to influencers

There’s something about the sweet spot that writing occupies in my mind that affords me some degree of consistency with publishing what I make. Here’s a potentially controversial take: the pinnacle of discipline-driven consistency in the domain of the arts is TikTokers. Whatever you think about the quality of their art, its impact on society, its validity as an artform, a few things are certainly true.

The vilification of TikTokers is driven by many concerns, among them: our profligate consumption of brainrot-causing content, our helplessness versus the organisations worth trillions of dollars that propagate this content, the obviously detrimental impact this content has on our shared culture. All these concerns are perfectly valid, but I must admit, I also see other less valid drivers of our scorn.

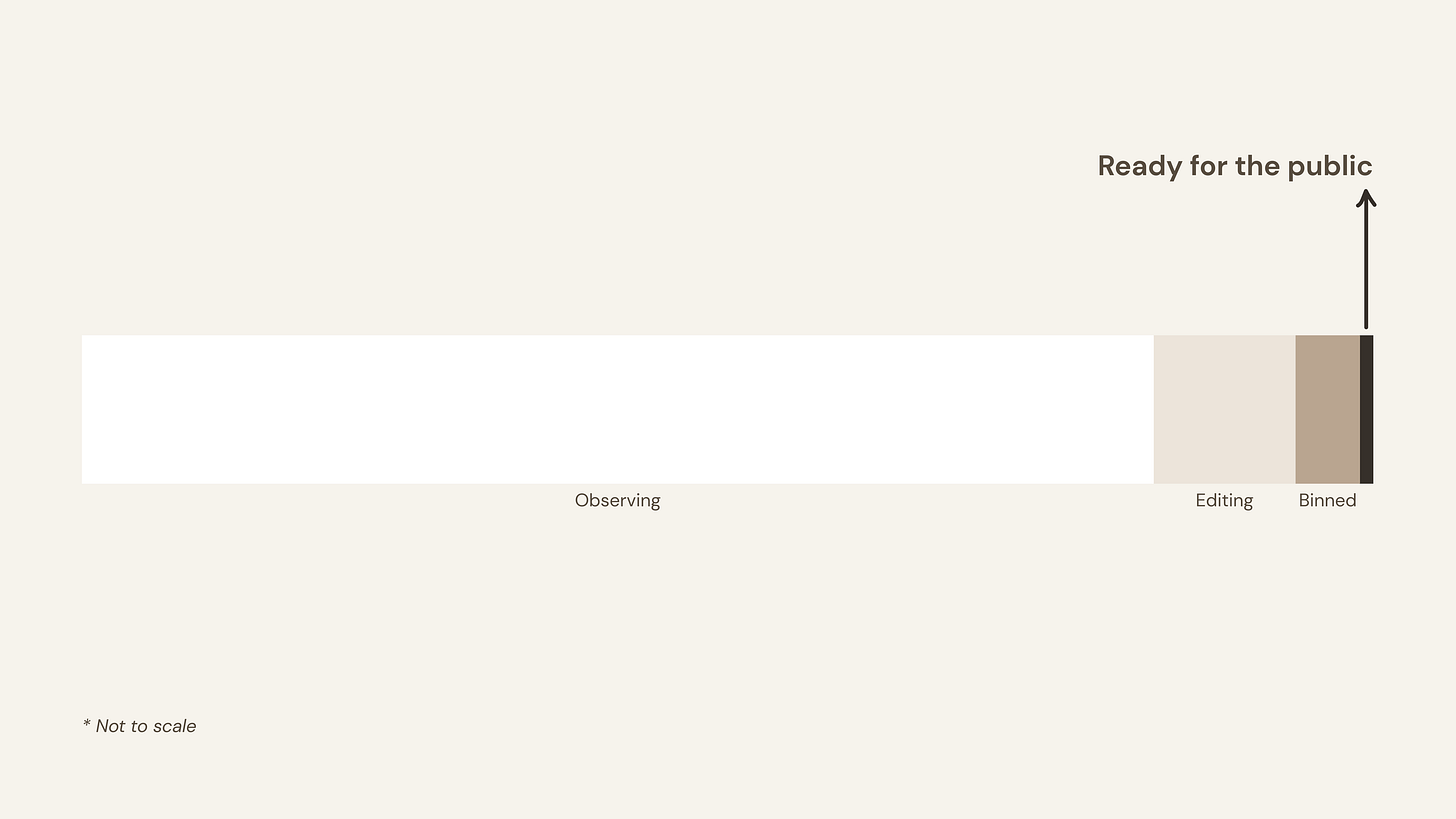

Firstly, we mistakenly think creating art must feel like how it feels to consume it. It does not. For every hour of consumption-ready art, there’s likely five binned hours of consumption-unready art, ten hours of making the one hour that’s worth consuming worth consuming, a hundred hours of practice, presence, observation. That is, for every hour of ‘sexy’, there’s maybe one hundred and fifteen hours of ‘unsexy’.

Secondly, we think of our own discomfort in laying out parts of ourselves for others to see, what our brains do to the rest of us when we’re, say, swimming. Then we think of the parts of others they have no discomfort sharing, and we project. They must be shameless, we think, perhaps unconsciously. Because, for the overdriven, every moment is a public moment. And for overdriven makers of products and things, the publishing moment, even if it involves nothing more than a story about a dinner party with friends, is anxiety-inducing.

When we get a peek behind the proverbial curtain on influencer exposés that show us that these influencers have had to reduce the remainder of life to make space for the ever-expanding space their craft occupies in their lives. We are righteously dismayed. But here’s a question: would we react in the same way to Joan Didion’s writing schedule? Would we be shocked that she built her life around her craft?

[More in part 2 next week]

It’s an odd thing to deconstruct, but then again, so is most of what I deconstruct. That could be my personal brand if this newsletter takes off: he deconstructs things that are odd to deconstruct.