Ready for Consumption – Part 2/2: The Publishing Habit

What sharing Out of the Hermitage is teaching me about product, market, and fit

You can find part 1 here.

Why I find publishing music stressful, or: why I think the world is unfair to influencers

There’s something about the sweet spot that writing occupies in my mind that affords me some degree of consistency with publishing what I make. Here’s a potentially controversial take: the pinnacle of discipline-driven consistency in the domain of the arts is TikTokers. Whatever you think about the quality of their art, its impact on society, its validity as an artform, a few things are certainly true.

The vilification of TikTokers is driven by many concerns, among them: our profligate consumption of brainrot-causing content, our helplessness versus the organisations worth trillions of dollars that propagate this content, the obviously detrimental impact this content has on our shared culture. All these concerns are perfectly valid, but I must admit, I also see other less valid drivers of our scorn.

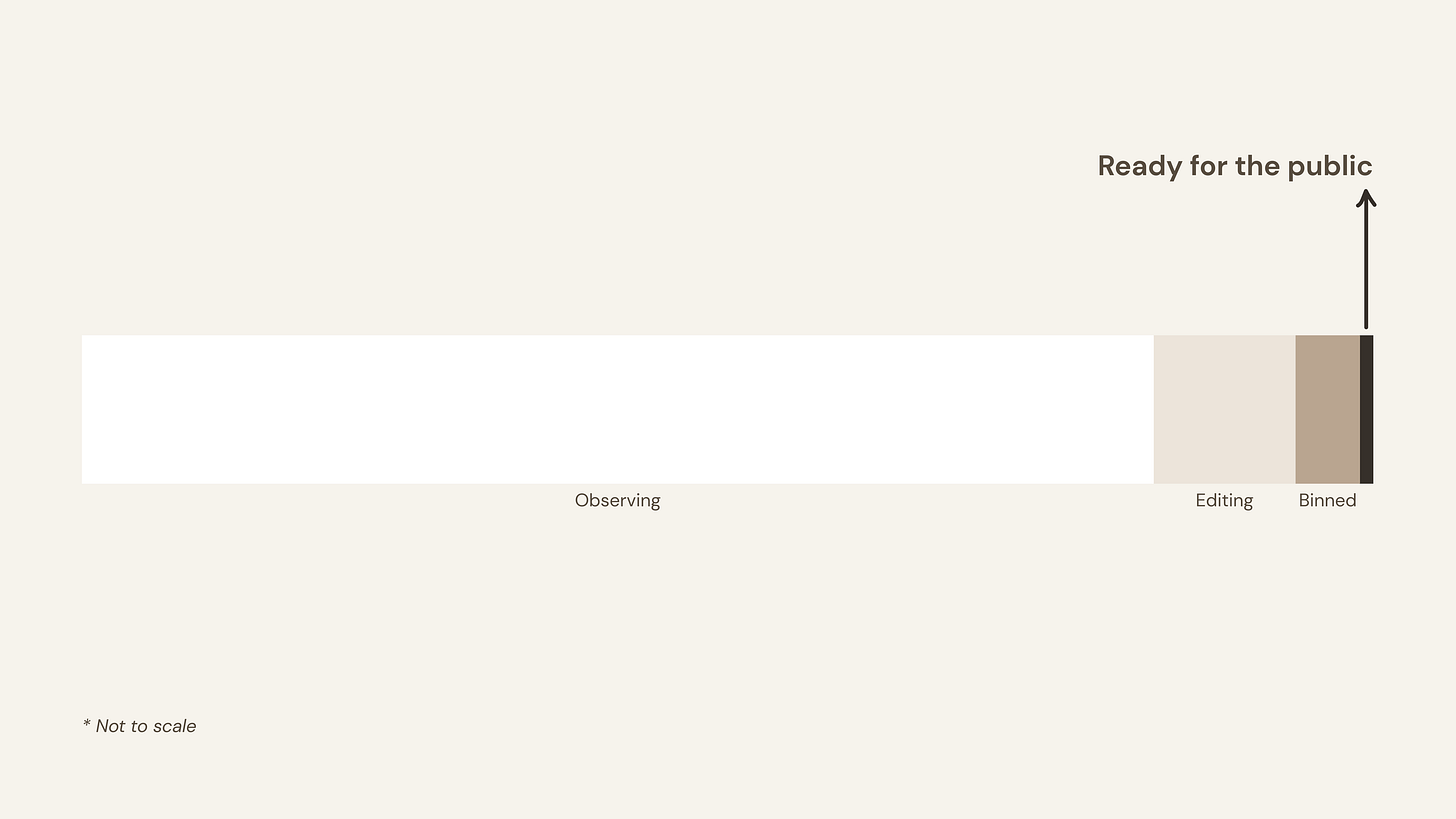

Firstly, we mistakenly think creating art must feel like how it feels to consume it. It does not. For every hour of consumption-ready art, there’s likely five binned hours of consumption-unready art, ten hours of making the one hour that’s worth consuming worth consuming, a hundred hours of practice, presence, observation. That is, for every hour of ‘sexy’, there’s maybe one hundred and fifteen hours of ‘unsexy’.

Secondly, we think of our own discomfort in laying out parts of ourselves for others to see, what our brains do to the rest of us when we’re, say, swimming. Then we think of the parts of others they have no discomfort sharing, and we project. They must be shameless, we think, perhaps unconsciously. Because, for the overdriven, every moment is a public moment. And for overdriven makers of products and things, the publishing moment, even if it involves nothing more than a story about a dinner party with friends, is anxiety-inducing.

When we get a peek behind the proverbial curtain on influencer exposés that show us that these influencers have had to reduce the remainder of life to make space for the ever-expanding space their craft occupies in their lives. We are righteously dismayed. But here’s a question: would we react in the same way to Joan Didion’s writing schedule? Would we be shocked that she built her life around her craft?

See, the publishing moment is different from the making moment. The sanctity of the making moment is contained in its authenticity – only possible in private. In the publishing moment, you desanctify it, before reimagining it in public: assigning it a whole new kind of sanctity. Will others benefit from this?

Value

That’s why it’s so much easier for me to put my writing out, or to go sell the services of Milk Toast Solutions to clients, investors, team members – or to play live with Ravens – than it is for me to publish the songs contained in Out of the Hermitage. It’s why I’ve chosen to write about my struggle in knowing when to publish Out of the Hermitage rather than the other – lesser – struggles.

With writing, with Milk Toast, with Ravens, the value of the publishing moment compares to the authenticity of the making moment. With the writing, having to find the words – no matter how idiosyncratic – to express myself in a way a non-Akhil person will understand necessitates a sort of process of ‘desanctification’. The act of taking abstract ideas and giving words to them – articulation – demystifies them. It concretises them. The reader is never truly distant. Therefore, the public moment is sacred. If you help one person with one thing you write, it’ll be worth it, I think. It isn’t about the likes you garner, it isn’t about whether what you writes resonate with one person. If it changes the course of one facet of their life by 1o, it’d be worth it. Here’s my hypothesis: if one can’t find as much sanctity in the publishing moment (value) as one does in the making moment (authenticity), the struggle to publish will always be there.

That’s why I find the publishing moment easy with Milk Toast. Actual clients, investors, team members make it very hard to shroud the creative impulse in an air of mystique. Every private creative act is soon a public performative act; it usually takes the form of a sales pitch. The feedback loop is immediate, often commercial. In fact, the hardest challenge in the domain of business is the opposite: to retain any sense of sanctity at all in the publishing moment. To remind oneself of the value-accretive act that business is meant to be. It’s so easy to get lost in the too-real and think of business purely through self-centred terms. The purpose of a business is to generate 1 million dollars in income for me, for instance. Or in the corporate world, the purpose of my job is to get promoted to VP, Commercial this year, for instance. In this worldview, there is no private creative moment, so there’s no sanctity of the private making moment – one tends toward inauthenticity, or worse, fake authenticity (yech). The bar for the sanctity of the publishing moment is therefore zero – there’s no bar. This manifests itself in all-too-familiar behaviour. We all know the type: that dude will sell anything to anyone anywhere if it means he gets ahead. Sometimes this person is your boss, sometimes it’s someone in your team, sometimes it’s the SaaS solution salesperson sat across from you, sometimes it’s you. The sad reality is that so many of us drone through our relatively prosperous white-collar lives with nothing stopping us from seeing life as a profit-maximising venture for the self: judging the relative worth of our work through the salaries we’re paid, our stock-based-compensations, etc. That’s the risk with work: that we forget the sanctity of creativity entirely, and therefore sell utter garbage to get ahead. With Milk Toast, I’m lucky; I find it easy to fight against that urge.

I find the publishing moment with Ravens, my band, to also be very easy. As a band that covers songs from our youth, Ravens is a performance-first creative endeavour. The publishing moment is very much baked into the making moment. And just like with business, there’s other people involved virtually immediately. There’s the band – jam sessions are a real trial-by-fire for any idea. There’s the audience – gigs are realer than jams. And then there’s organisers, venue guys, sound guys, all sorts of guys that are core to the process. By the time a band becomes a touring, recording band, it resembles a business like Milk Toast way more than it resembles the private creative moment of music composition I had described in part one of this essay. The risks resemble the risk of business way more than the risk with a project like Out of the Hermitage. The risk of selling out.

In conclusion: Make then sell, or: the publishing habit

So.

How does one answer the question: When does ‘ready’ mean ‘ready for the public’?

First things first, you’ve got to keep making things, no matter how uncomfortable you are with the idea of other people discovering the things you’ve made. It is so easy to lose the making habit. How often I’ve lost it in the past. How much effort it takes sometimes to just get oneself to sit at a desk and scribble or type – even if just for a bit. If I hadn’t recorded all these songs over the last four years, packaged them together – in my mind, at the very least – as Out of the Hermitage, there would be no dilemma to solve. That’s the worst outcome.

Here's three useful tactics when faced with a daunting making moment.

Tactically, any sort of ‘making’ requires a mental shift from inspiration to discipline. Inspiration is needed to spur action in the first place. Discipline is needed to continue.

Our modern lives make making things difficult. Our brains are never truly quiet, and any act of making requires focus; that’s a bad combo. Set. Your. Phone. Away.

The making moment is not the selling moment. The building moment precedes the showing moment. Build first. Worry about show-and-tell later.

To begin with, discipline is a tougher fuel source to tap than inspiration is. It’s so much less fun too, at least for me. It burns more slowly, less bright. That the answer to creator’s rut – like writer’s block – may be routine, sounds so horribly unspontaneous. It sounds… well, routine, run of the mill, prosaic, blasé, blah, take your pick. You power through the first several weeks of the building process purely on inspiration. Everything feels fresh, citrus-y, maybe you’ve told everyone you know about this cool new thing that you’re building – maybe it’s a product, maybe it’s a newsletter, maybe it’s a novel. How wonderful, everyone you’ve told replies. Good for you, they say. The greatest hits of validation follow: I wish I could do what you’re doing, I always knew you had it in you, if someone can it’s you. Hit after hit after hit after hit. Best wishes shared, copious amounts of help offered, contacts shared, etc. etc. And then… silence.

Building anything that matters requires a string of silent, unsexy hours. I’m not talking about successfully selling what you’ve built, which involves unsexy hours that are loud and public as well: failure, rejection, ridicule, it’s all part of it. I’m only talking about what building requires. No matter how much you love what you’re building, for the most part, labours of love aren’t created by love; they’re created by labour. On some level, we all know this to be true. Our shared image of the architect is of someone who is hunched over a three-dimensional model, alone. Our shared image of the developer is of someone whose half-asleep face is lit by nothing but an array of monitors. Our shared image of the writer is of someone sat at a desk, alone, scratching away at a piece of paper, balling it up, throwing it away, going again. When we think of makers, we don’t think of ribbons cut outside glistening facades, black turtlenecks sported on dimly lit stages, awards being accepted. Those are the images our brains conjure up when they think of celebrities. Celebrities ≠ Makers.

And as for the daunting task of treating your labour of love with respect? Not smashing it to bits in your own mind before anyone else has had a chance to even see it? The solution may be contained in something Ernest Hemingway is said to have said: write drunk, edit sober. To be clear, I, a sober guy, am not endorsing drinking. As someone who is aware of the life Ernest Hemingway lived, I’m certainly not recommending one drink like he did. It’s the principle that I’ve found works wonders.

When in making mode, create (‘write’) without inhibition, as if drunk. When in publishing mode, prepare for the eyes of others (‘edit’) not only as if sober, but as if no longer drunk. Through now sober eyes, analyse what isn’t good – commit to getting rid of it. Through now sober eyes, analyse what must stay – commit to improving it.

Making needs no audience. In fact, an audience is detrimental to the act of creativity. That’s why new products are first built for a small set of alpha users, internal testers, then moved on to a set of knowing closed beta users, folks who have context on the intent of the product, then an open beta set that is forgiving of kinks that need ironing out, enthusiastic to point out ways in which the product might improve. Only once they’re ready, are they released to the world. I remember Jonny Ive, the designer of the iPod and the iPhone, saying in an interview with Stephen Fry: ideas are fragile things. Indeed, they are. They break at the slightest bit of contact with the elements.

The publishing habit is tough for the same reason I would recommend a life of influencerdom only to those capable of handling the attention that comes with success. For everyone else, the eyeballs of others will eat you alive.

An unpopular upgrade on my previous unpopular take. Those who hold strong anti-influencer views likely have a very broken image of themselves. This is true even if you think influencers themselves likely develop a very broken image of themselves from the time they spend on TikTok. And that nobody but the already attention-hungry should choose a life of influencerdom. The thing about culture is that it finds you in your nook; you can’t escape it.

We think content creators overcome the discomfort of the publishing moment because the gratification from posting content online must be far greater for them than the discomfort. This gratification, we imagine, is in the form of money, dopamine hits, ‘bad things’. I say ‘we’, because this is my only explanation for why I have hours’ worth of unreleased music. Because I do not respect the value art of that variety adds to its audience. On some level, I think of my music as equivalent in value to a reel or a TikTok, and I think both these artforms are without value.

Even though composing that music provided me emotional sanctuary precisely when I needed it most, precisely in a way that nothing else could. Not even writing, which I publish with far greater consistency, even if it’s far more deeply personal in nature (take this essay, for instance). It isn’t the fear of rejection, which surely must apply more deeply to the writing. It’s self-judgment. You’re pimping out a moment of such great spiritual significance for what? Attention? That moment’s yours. Why are you sharing it with strangers? It’s this judgment that we direct towards influencers, caring little about the comfort they – and their audiences – might have received from their TikToks.

Find your driver elsewhere: away from the eyeballs of others, and instead in their hearts, their minds, and the publishing moment doesn’t feel disgusting anymore. It feels sacred.

All this is to say the following: the next post will contain the first Out of the Hermitage release – an acoustic folk cover of 1979 by Smashing Pumpkins. All future releases will be found on Stranger Fiction, which is a magazine I publish; maybe it becomes an edition within this newsletter in future. Who knows?